There is a joke among game-makers: why make a game? For fun? For money? Or just out of stubbornness or because “no one has made the exact game I want to play, so I have to make it myself”? And this story is one of those…

Me, Mark and Dezful

I was born and grew up in Dezful, a small city in Khuzestan province. In this city, whichever group or gathering you go to, one of their pastimes is getting together and playing cards especially a custom version of Shelem that they call “Mark”. From about age 12-13 , I also sat “behind someone’s hand”* and watched others play until I entered the adult arena and became a more serious player.

When I was a student, sometimes in the afternoons or evenings we gathered by the Dez river and played. Then when I moved to Tehran for university, I continue to spent part of my time playing Mark with some friends. Generally our group’s fun was cafe, PlayStation and hanging out, but whenever four people from Dezful were in a group, there was no doubt that our fun had to be Mark.

Sitting behind someone’s hand

Means watching someone play, sitting behind them, trying to understand how they make decisions and asking them your questions

If I speak more honestly and precisely I wasn’t really a big fan of this game from the start. Even always on our friendly trips and journeys I made a condition that not all the time should be spent playing it. I even remember once on a trip to Bushehr when we arrived at the destination my friends started Mark and continued until midnight and I became annoyed and a short argument took place.

But things don’t stay the same forever. Time passed and I moved to the Netherlands, as a consequence playing Mark was no longer a choice but a force which was bothering me, mostly because of missing friends and groups for good old days.

I don’t remember exactly when the idea came to me, but around spring 2024 I became more determined that I should dedicate part of my time to making this game. And as you know the hardest part of such decisions is not deciding! It’s the start, the commitment and the consistency in that work.

Working without thinking means a miserable failure

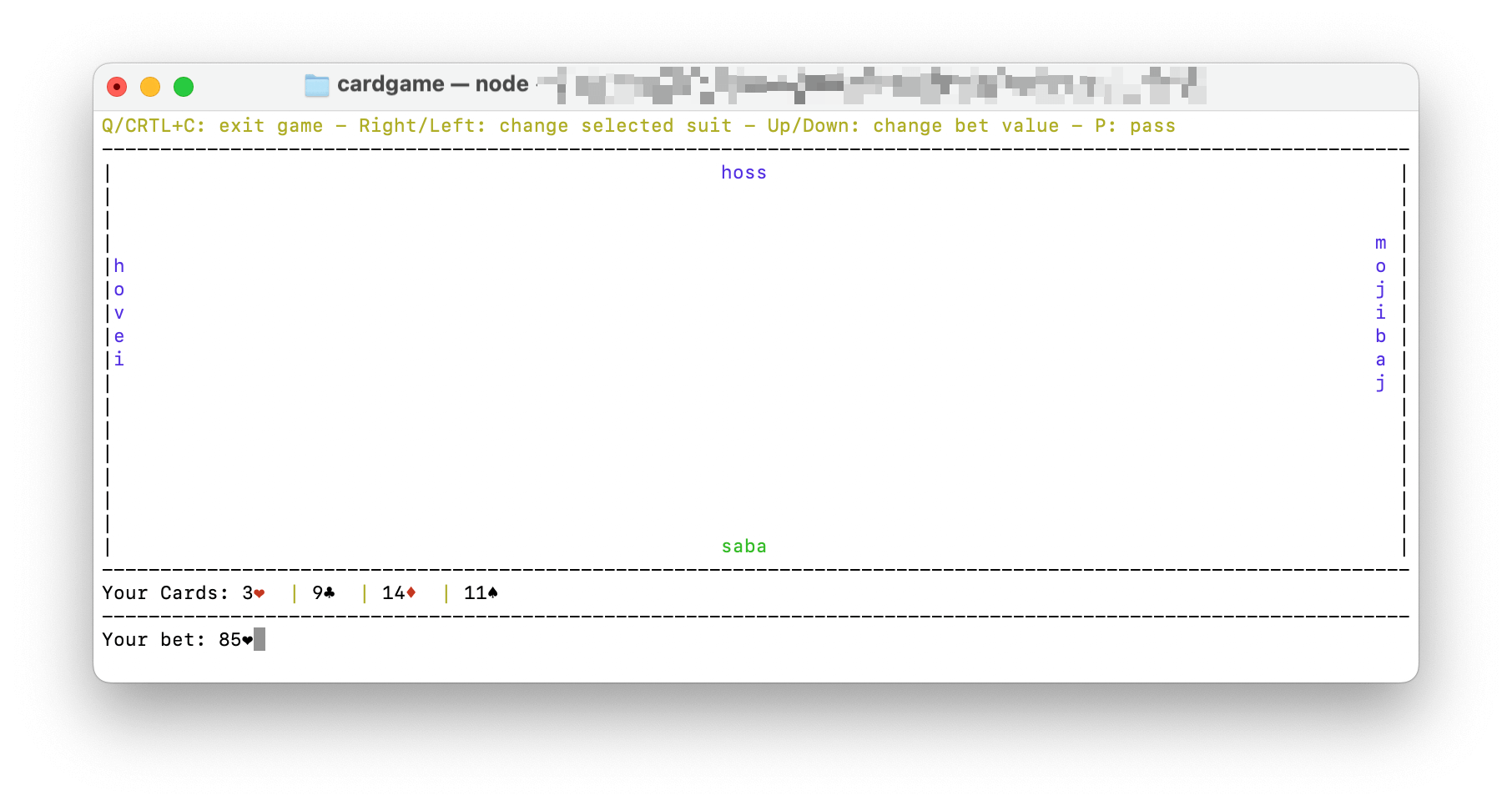

In that rush and excitement of the initial idea I thought: I will make a terminal game in the style of old games. Honestly I laugh now that this was my first decision, but at that time for my mind it seemed really interesting and cool. Also I had the thirst to learn this, so I went ahead and made a terminal game using TypeScript. I played with it for a while and the first look came out nice imo. But in a self talking moment, I realized let’s say I made it who is going to play this? I can’t force all my friends to open their computer each time and teach them how to use the terminal. So I closed that method’s file right then! In short, I failed very quickly, less than a week, jeez!

You can find its code here: GitHub

Let’s think properly

After that stupid idea I chose to do a better planning. My first step (and also many others’ step) in designing & developing a software is the pillars of that project. You must have some main pillars you stick to. There is no strict rule for them and it depends entirely on the project, goals and personal preferences. Their presence makes decision-making easier for both small and large ones.

If you’re not familiar with “design pillars”, let me give you an example: Suppose one of your project’s pillars is “fastest solution” and you require a caching system. Naturally, there are many answers and tools: the simplest might be creating a Map in your code up to launching Redis or Memcached or other tools. Now suppose your programmer doesn’t know any of these tools. Then the path ahead is: use the simple Map, or spend time learning one of the other tools. That choice and learning is itself not simple, because you also need a decision about which one to check, which is more suitable, and finally you need a proof of concept to pick and implement one. See how complicated it becomes? Now in this condition you go back to the pillars and you see that one pillar is “fastest solution”, then the light bulb turns on and there’s no more discussion: the fastest solution means the programmer uses something simple right now and projects moves on and upgrades later if needed. The presence of pillars in your project can greatly speed your decision-making and thus your development. If you’ve never worked on a large project you can’t imagine how people encounter even simple systems during implementation and of course in the absence of these pillars the project gets locked in strange ways.

So now that I said so much — what were my project’s pillars?

-

First: This is a fun/personal project, and it doesn’t matter how long it takes. If I miss the deadlines I set for myself, that is okay. For me it is more important to enjoy making and releasing this project → this means there is no stress for me on the project and no guilt for delay.

- Second: My goal in making this game is learning and self enjoyment. So whenever I see an opportunity, I park the project for a while and go learn what I need → this means I don’t settle just for things I know; if there is something I don’t know but I like and I have patience, I go for it.

- Third: It’s not necessary to satisfy all user requirements → during the project many ideas and opinions appear and a person naturally wants to cover them all, but that list is long and causes overload. So: whenever someone gives feedback I note it but that does not mean I will always implement or apply it.

- Fourth: Current needs must be covered and I should not over-engineer for future needs → this means from the very start I don’t think “if 10,000 players play at once what will happen?” or let’s make 10 microservices or …, I only focus on covering 10 simultaneous players (my friends) so don’t over-engineer and chase solutions for problems that don’t yet exist.

As you see the pillars weren’t very special or strange they only gave me a roadmap for making decisions more easily. Which pillars do you set in your projects? (In the style of Instagram influencers?)

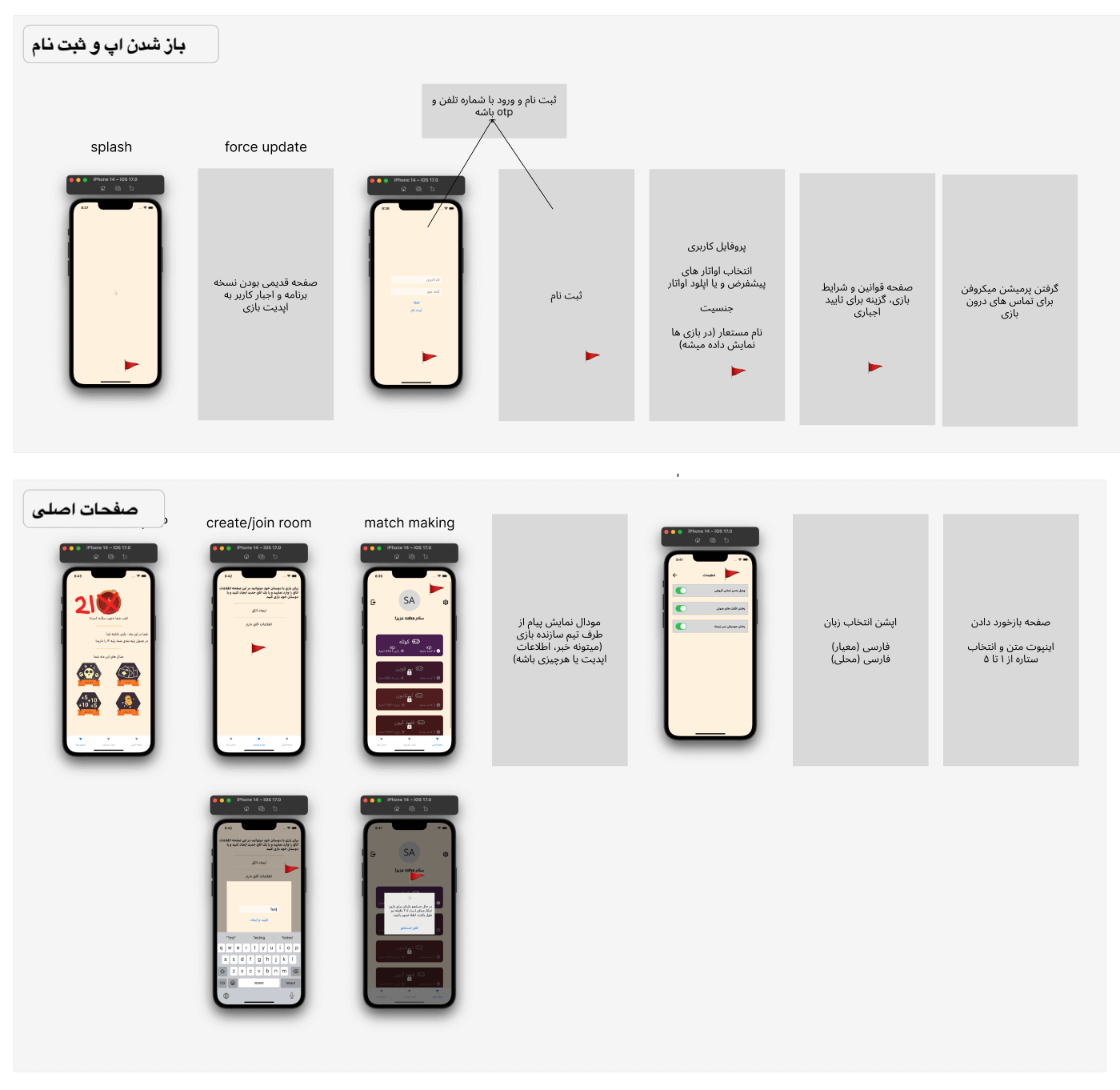

Think logically

Since that spirit to make this project was still alive, I decided to build the game with React Native. Why RN? Because it’s a tool I had worked with for a long time and I’m well experienced with it as a result I could move fast. Also I knew everyone has a mobile in their pocket nowadays and I don’t need tp train people how to install and use the game. I decided not to bring a designer/artist into the project at the beginning and try to make a prototype of the game.

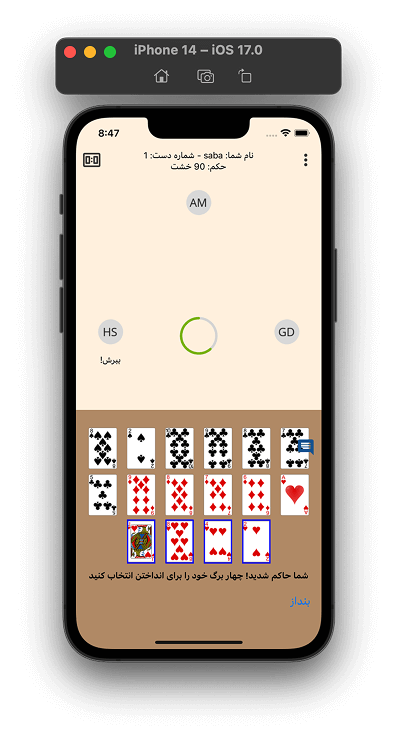

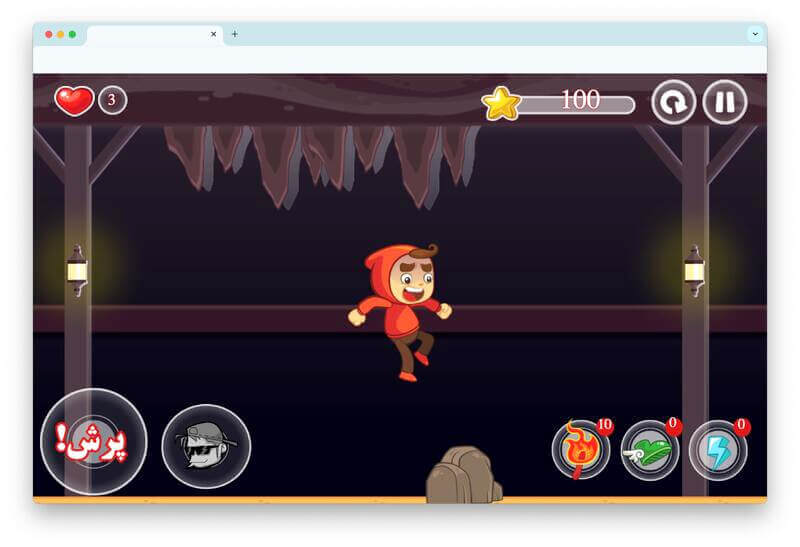

It took some time until this coding phase ended, but finally the general appearance of the work was ready and a very good base for further work:

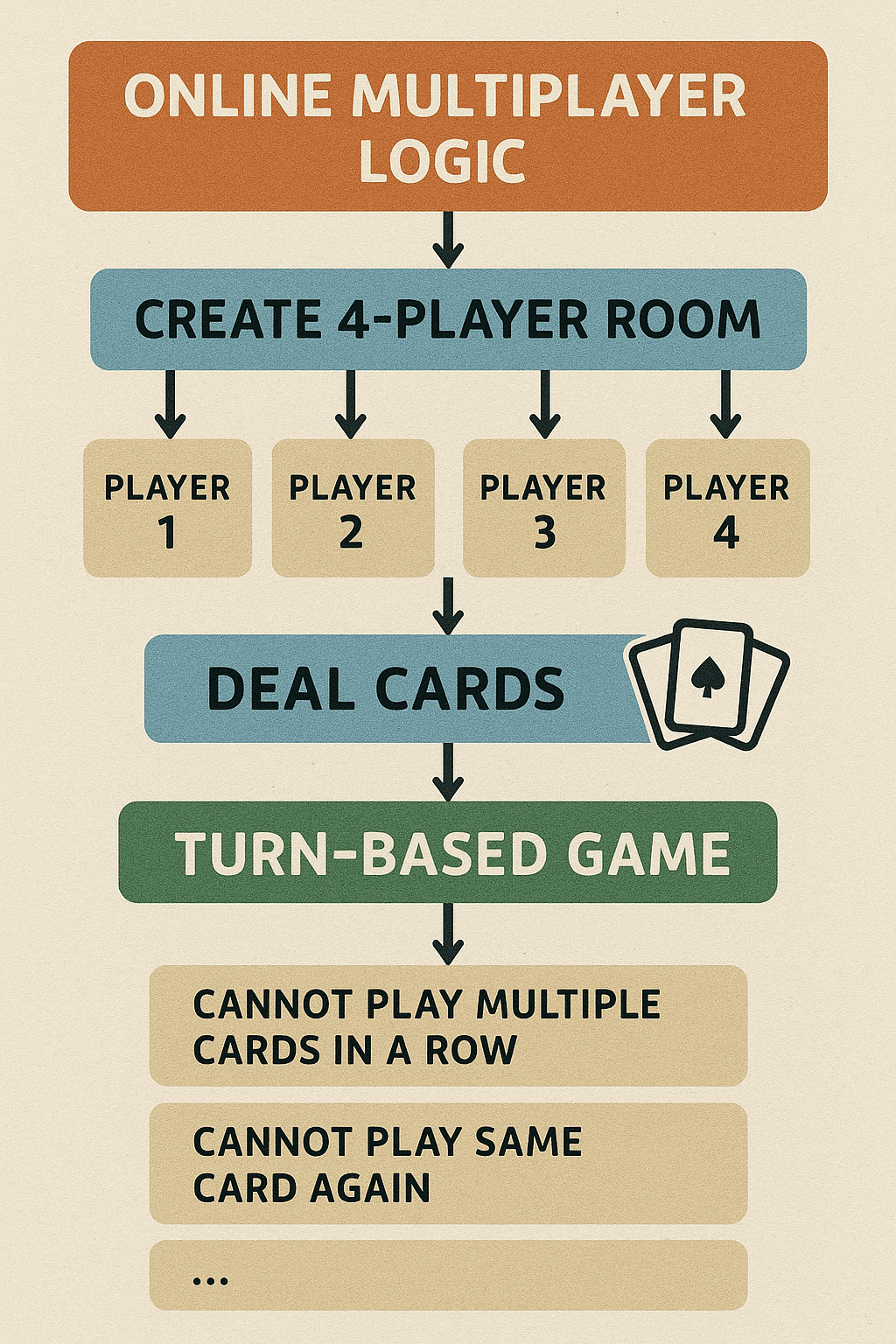

Now the project had reached the stage where the online part and the general logic of the game had to be done. The idea was: a room of 4 people must be created, players connect to each other, cards are dealt, naturally, no one should know the hand of another player, it’s turn-based and no one can put down several cards in a row, no one can re-throw a card they have already thrown, and so on. But how do you really implement Multiplayer for such a game? This was my first experience for such a thing and once again a good learning opportunity.

In general for a game like this there are a few questions that needs to be answered:

- Where does game authority live? Which machine enforces the rules, generates randomness, and validates moves? server or host

- What do clients exchange? Inputs only, actions, or partial/full state?

- What is the network topology? Do players connect peer-to-peer, through a server, or hybrid

You can guess that each of these has its own advantages and disadvantages, and depending on your goal and your work one of them might satisfy you. For this project I went for:

- A fully authoritative server to run all game logic and prevent cheat

- Exchange player actions, like DROP_CARD and TEAM_A_WON

- Client–server networking, so all players connected to the server

Once the method was chosen, now it was time to implement a near-real-time server. The easiest and fastest way would be using services like Firebase but that option wouldn’t work because for my friends it is blocked and it wouldn’t be wise to force users to need a VPN from the start. The next option I had personal interest in was to write this part using Go and WebSocket for client–server communication. But after thinking I saw that in both of these I had some experience but not professionally, and learning two new things at once might be too challenging. So I decided to develop server in Node.js (which I had a lot of experience with) and for the socket I used Socket.IO. The main reason for choosing SIO was the active support and high usage in many projects over the years so it’s “battle-tested”.

As you can already guess, this project also needs a database, right? In those days I was working with MongoDB daily and I knew it would answer more than my current needs, especially because I didn’t have structured schemas yet and NoSQL gives you this flexibility to push data without strictly defined structures. This flexibility was important for me because I didn’t have a fully clear data-model and I didn’t want to stop the project to get perfect models (which can cause major issues in the future but after all this a personal hobby project). On the other hand working with Mongo increases my own knowledge and would help my daily work at company, one arrow and multiple target hits.

Since I had prior experience with Socket.IO on the client side, learning SIO on the server didn’t take much time and backend development was fast. The next phase was the wiring between app and server. These two stages took about 5 months, this time may seem long but since I was working one day of weekend and sometimes evenings/nights some days of the week, it was acceptable.

Meanwhile I needed fun and travel too and couldn’t spend all my time on the project because I’d get tired and might be burned out (and that could affect my daily job). I believe for doing side-projects it’s important and necessary to have make a balance.

Finally everything was ready for the first test of the game by others, but I felt something was missing. The game itself was good and working, but a big part of the fun of Mark is the trash-talk and banter; an app that just shows you some cards and you click on screen doesn’t feel alive. So I decided to delay the release of this version until I add voice chat. The sensible approach was to use Telegram or WhatsApp or Instagram for voice chat but those were all blocked in our country at the time, and also I had found something new that I could learn.

The VERY BASIC and over simplified theory of building a group-call system over the internet is to take the microphone audio buffer from the user’s device, preferably compress and encrypt it, send it to the other users in a fast way, then decrypt and play it.

WebRTC

I had heard about WebRTC many times but never had a real reason to use it. When I finally decided to add group voice chat to my game, I started looking into what WebRTC actually offers — and realized there are three main approaches:

- Using a voice-chat SaaS provider such as GetStream. These services give you an SDK and handle signaling, TURN/STUN, mixing, scaling, and permissions. It’s basically “audio calls with one import.”

- Pure peer-to-peer WebRTC, where every client connects directly to every other client. This is simple in concept, but the upload bandwidth grows fast (N-1 streams per client) and reliability depends on NAT/firewall conditions.

- Using an SFU/MCU server, where clients send one upstream audio stream to a server, and the server distributes or mixes streams.

Since I enjoy building things myself and had the time to experiment, I decided to skip the SaaS option and explore both P2P and SFU models. This led me to Janus, a lightweight C-based WebRTC server. Janus acts mainly as an SFU, clients upload only one audio stream, and Janus forwards it to the others. This reduces upload pressure, especially in low-bandwidth or high-latency environments, which is important for users who are not on stable connections.

Learning and understanding WebRTC, learning Janus and its setup, and client-side implementation took me about one and a half months but the result was satisfactory and I finally had in-app group voice chat. I hope one day I will write more about that experience too.

First play

Without telling my friends what this thing I sent was, I gave them the first version. I had also placed a simple lock screen for the server side. They installed and I removed the lock. They were shocked and their first feedback was funny and cool. That night we played a couple of rounds and it was one of the coolest moments of my life. After about 1.5 years I could finally play with my friends again.

This version had many bugs and many rules were not implemented yet but feedbacks let me know that I am going in the right path and probably more people will enjoy this game. The interesting point is that the group-voice feature is no longer there now and I don’t think I will add it anymore. What remains for me from that time is the recorded voice from the first game and the experience of working with WebRTC and Janus.

It was time for proper design

Once a number of games were played I wrote for myself a longer-term plan of features and problems list. It was at that moment that I created a Trello board and did things in a more structured way. From the planning to implementing the items I considered important took about 1-2 months. Now the game was ready and working, though still ugly and I felt that now was the right time to get a proper design.

Finding a good designer / artist for this project was challenging because these days many designers work in a minimalist style, and in my opinion this project suited more traditional designs and graphics and finding an artist that does that style in Persian was not an easy task. After a long search, messaging different people and discussions, I finally found Erfan, a skilled Game Artist whose portfolio had designs similar to what I was looking for. First I sent a LinkedIn message and waited a week, but no answer; so I emailed and fortunately he saw my email and finally agreed to do the designs for this project. I also prepared a Figma file of all current pages and pages not yet existed; and together we created a mood board so he could better understand what kind of style I wanted and finally the work started and for a while I had free time.

Although I had implemented the server side pretty simply and cleanly, the RN project’s code was very messy and barely maintainable or scalable. I don’t blame myself because until here everything was exploratory and the goal was simply to make a usable version. Since I always had interest in serious learning of game-engines, I decided instead of rewriting in RN, I would implement a new version with one of game engines. Naturally Unreal was too much, Unity was out of options due to some decisions in recent years; the two remaining options for me were Phaser and Godot each with their own pros and cons. With awareness of the limitation of full WebRTC support (and naturally if I could not find a good solution I’d give up the voice chat) I chose Godot and learning it went into my plan! I think it’s worth pointing out that I had previous experience with creating games using game engines and my familiarity with these helped me a lot to learn Godot faster.

Implementation in Godot

Learning Godot was straightforward. Its scripting language, GDScript, is very similar to Python; it also has official support for C#. My first decision was to use C# because of its wider tool-library like Socket.IO but in tests I found it is not compatible for Godot and the C# code sometimes annoyed me and reduced my speed because of its compiling nature, so I decided to go with GDScript and implement everything I needed myself. Since there was no Socket.IO for Godot I wrote a minimal version myself (and published it).

The only part I tried but could not implement was the voice call that I was already prepared for. With this library I could capture audio buffer in Godot (though had some issues on Android) but the problem was sending it to server/other users because current WebRTC implementation in Godot does not support media. My first attempt was with MQTT which did not have enough speed (naturally because it is TCP based), then I decided to send the data via Janus DataChannels but the Janode library (which is a NodeJS package to manage Janus) did not support “Text Room” at that time. It took a few days to implement a Text Room plugin for Janode and I managed to get audio working. Basically it was creating a TextRoom and then users connect to it, each device base64-encoded its audio buffer and sent it to Janus, the others received and decoded and played it back. But performance dropped significantly (especially on older phones) and the effect was noticeable eventually I accepted the failure for now and removed the voice call feature to revisit it at a better time. Interestingly, I had planned to submit the TextRoom implementation to Janode but I got busy with other work and some time later they implemented it themselves. A lesson: if you write code you must publish it sooner.

Erfan’s work was finally completed in the best form and with full satisfaction from me, now it was time to implement. Implementing all pages in Godot took about 2.5 months, then after some smoke testing I wired the game to the server and now it was possible to play and enjoy.

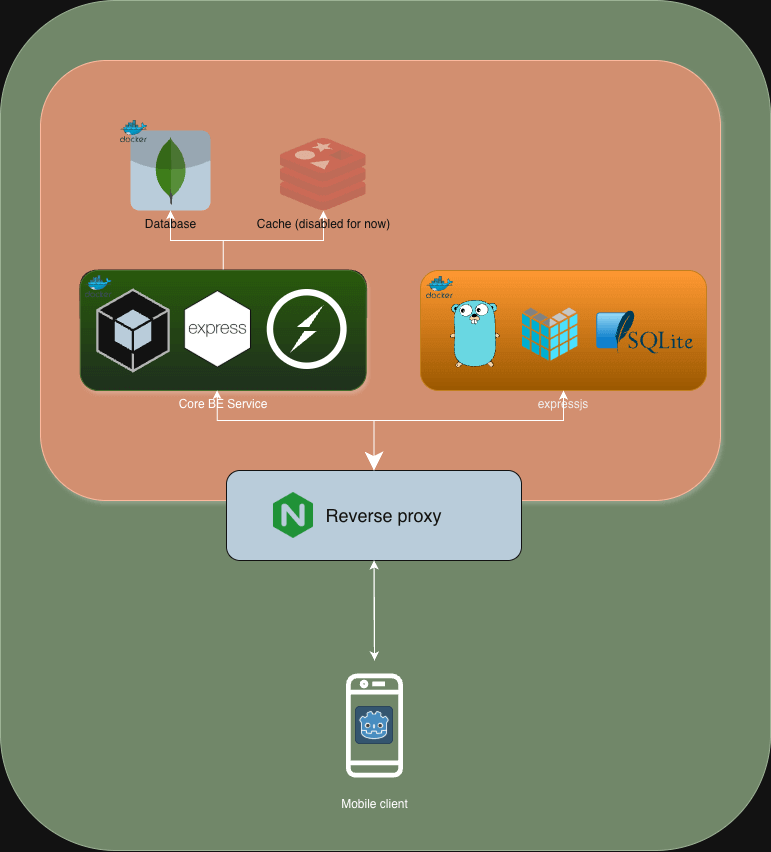

Although it was time to distribute the game to alpha testers, I knew being blind to how your users use the app is one of the worst mistakes, so I decided to add a Logging/Tracking and Crash Analytics to the project so that when someone hits a problem I can use the collected data. The problem was: none of the well-known tools (like Sentry or Firebase) supported Godot. The other systems were either paid or I was unsure about their mechanism. Finally I thought: what a great moment for learning and I went for Go this time. I built a separate service called “Track” with Go which stores client track events in a SQLite database. These data are not that important and are deleted every few days via Cron; the main objective for me was having a way to see user interactions and find problems that users have. Now the project was ready: much prettier and had many new features. The only thing it lacked was an AI to play against the computer which at that moment didn’t seem too critical.

Hello World and Beyond

I posted a story on Instagram asking who wanted to test the project, and around 30 people showed interest that same day. During the next week, about 30 more friends, acquaintances, and sometimes friends-of-friends messaged me, and I gave them access too. The testing phase officially started, and every day I was receiving different messages and voice notes about bugs and things people needed. I added all these feedbacks to my Trello board, sorted them, and set priorities. I also created two WhatsApp groups so we could coordinate with different groups and play together. One of these groups with my own friends still exists today. Every now and then someone sends a single “dot”. A dot means “I’m here and ready to play,” and when four people send dots after each other, they start a match. From that first day until now, seeing those dots and the game stats gives me joy and a very good feeling.

For the game’s AI, two of my friends spent some time and we got some results but it didn’t reach the level of maturity we wanted. Then they got busy with their life, so unfortunately the AI work stopped. With the help of ChatGPT and some similar open-source card games (Hokm and Shlem), I implemented a simple decision algorithm with if/else and a value table. For now, it works well, although sometimes it acts really stupid but it’s good enough imo.

After removing the voice-call feature, I didn’t want the project to feel soulless, so I contacted a local narrator. We agreed that he would record some voice lines for messages and events inside the game. This part turned out very well and is one of my favorite features. And this is how, after a testing period, the project reached a more stable version and I think the job is done.

Finally, I rented a VPS, installed CapRover, and now the database and all server-side code are hosted there. The current diagram looks like this:

Future

Right now, while I’m writing this post, the project is in Feature Lock mode. I’m not adding or removing anything, except for one exception: I’m waiting for a stable release of Sentry for Godot. When that becomes available, I will turn off the Track service and collect all logs in Sentry. After that, I will fully release the game.

For now, I have no plan for more development or monetization. I think the file of this game will stay closed for about one year. During this time, I can gather feedback and fix problems that are very important or very annoying. After this period, I will decide what the future of the project will be. But for me, I already reached the final personal goal of this project.

My guess is that after release, this game will get around 300 users and around 3 to 5 games per day. Later I will update this part and say how close my prediction was to reality.

Thanks

Thanks to Sara, she gave me the space I needed to work on this project and has been the spiritual sponsor of it. Thanks to Ali for the Lori translations, and to Mohammad, Hossein, and Omid for helping me choose the correct Dezfuli words. Thanks to my uncle Ali for playing several times a day and giving important and effective feedback. Thanks to Sina, Mojtaba, Mohammad, Alireza, Mehdi, Ali, Hossein, Parham, and many other friends who helped me test this game and gave very good feedback.

Thank you all. Let’s go play :)

I hope your side projects also reach the results you wish for.

EOF

Published on: 16 Nov 2025